What One Learned From Corbusier

-Address at the ‘Celebrating Chandigarh’ Symposium, Chandigarh,2002

The essay is sourced from the book A Place In The Shade, authored by Charles Correa published by Penguin India in 2010.The essay features on pages 63-74.

Some fifty years ago, when Chandigarh was under construction, Indian architects were often asked why we had not objected to Nehru appointing a 'foreigner' (i.e., Corbusier), to create the city. The question astonished me. I knew the Government of India could easily have selected some large commercial office for this assignment. Instead, what an incredibly good choice they had made! India was indeed lucky to get Corbusier.

Years later, when I visit a place like Dubai, I realize that the converse is also true: Corbusier was very lucky to get India! For here in India, he dealt with people who understood that architecture could change your life- an attitude that is fundamental to its creation. It is never a question of the size of the budget - but of something else, beyond finance. This is the essence of what we learned from Chandigarh - and why a poor country like Bangladesh can elicit a masterwork from Louis Kahn.

I

For me personally, it all started in the 1950s, when I was a student of architecture, and a tiny sketch of the proposed High Court was published in one of the architectural journals. From this one could form a general idea of the parti: four boxes for the judge's courtrooms, and a fifth double-height box for the Chief Justice's court. The concept seemed fairly comprehensible - but it did not prepare me in any way for what I saw when I actually got there. The huge parasol roof, the giant ramp crossing back and forth, and the most stunning tour-de-force of all: the great front wall of the courts, rising up in a huge sweep, like a hovering tidal wave about to crash on you. Apart from everything else, how on earth did Corbusier conjure up this wall? Cocteau thought that genius in art consists in knowing how to take risks. When all your friends tell you, 'Stop, it's perfect', 'that's when the true artist takes his chance.

With Chandigarh, suddenly India was centrestage on the world scene. Architects from everywhere came to visit Corbusier's buildings - and were profoundly influenced by the impact. So, when you got back to your own office, you wanted to redesign all your projects in exposed concrete - great sculpted shapes, cast in situ, using handmade formwork. Paul Rudolph in America, Kenzo Tange in Japan, the New Brutalists in Britain, all wanted to use a construction technology which was extremely esoteric and expensive in the United States and Europe and yet, for us here in India was a perfectly legitimate and economical way to build. This was adrenaline indeed! For by building here in our own country, we got the extraordinary opportunity to be at the cutting-edge of where it was all happening.

This launched contemporary Indian architecture on a trajectory that is fundamentally different from the kind of Disneyland mode (golden domes in the sunset) that many architects, even very good ones, seem to slip into when they design a building in, say, Saudi Arabia. In India, we have the confidence to know that a serious piece of architecture can be created right here in this region - and that it is up to us to dig in and find it. In fact, if you think about it, all great architecture, from the Oak Park Houses of Frank Lloyd Wright to the temples of Kyoto, is - in that sense - regional. The buildings speak to us powerfully and eloquently of their time and place - that is why they become universal. Those Wright houses in Chicago's suburbs could not have been built in London, or in Delhi. Like Chartres and Fatehpur Sikri, they are rooted in the soil on which they stand.

And the corollary is this: architecture is not a queue in which we all have to line up, with perhaps the Americans ahead, or the Chinese behind. No, each of us has the opportunity to be on the cutting-edge of where we live. No one else can do that. It's up to us to understand that opportunity.

II

Corbusier's work was truly magnificent. Using concrete with extraordinary power and flexibility, he had developed an architectural language that influenced architects not just here in India, but all over the globe.

And yet, of all the lessons one learnt from him, this was perhaps the most unnecessary - and dangerous - one of all. In fact, his language was so compelling, it takes one many years to climb out of that box -and does one ever really completely get out? Yet, the very process of borrowing his language was invaluable. It allowed you to experience, even if only vicariously, the expressionistic power - the decibel level so to speak - of great architecture. Later, while struggling with your own work, it was a benchmark helping you to realize how far you still had to travel.

Another crucial lesson we learnt from Corbusier was his attitude to the commissions he received. Now Corb might have been quite a different kind of person at the start of his career - as witness the obsequious flattery he showered on potential patrons ('O, ye Captains of Industry' and so forth), all just thinly disguised pleas for large commissions. But by the time he came to India, ye Captains of Industry had all failed to turn up. (What if the shameless carpet-bagging of today's China had taken place back in the 1920s, would Corbusier at least, the one we know - have survived?) No luckily for Corb, and for Wright and the early Mies, those large commissions just never materialized. And so all that energy, all those ideas, became even more intense, more rigourous, more potent. This gradually coalesced into the stance, so perceptively described by Charles Jencks in Corbusier and the Tragic View of Architecture as: 'No one is ever going to understand me, but I shall press on, regardless! Melodramatic perhaps - but for young Indian architects just starting out practice, it engendered exactly the kind of courage needed to stiffen one's spine - and block out any danger of selling out to the big battalions.

This attitude of Corbusier was reinforced by his rare understanding of the consecutive commissions that make up one's professional life. For unlike the poet and the painter, the architect is not really completely free to choose the problems he tackles. And once he embarks on the process, he can seldom back out of the project. The artist is different if he does not like the painting he is working on, he just turns it to face the wall, and starts on another canvas, perhaps on quite a different subject. But for us, to start a project is to become part of a socioeconomic process we cannot halt - for better or worse, we are riding a tiger. Which is why Corb's work is so amazing. Each project in those eight volumes of the Oeuvre Complet is like a consecutive step in a great broken-field run - those amazing feats in football and hockey where someone takes the ball down the entire length of the field to score. You realize perfectly well that the whole feat is ad libbed and yet when you see that goal again in a slow-motion replay, you are convinced that at every moment the footballer knew precisely what his next step would be.

Corb could make that touchdown because each step he took was determined not by the size of the commission, but by its relevance to his overall goal. Thus, La Tourette is just a small hostel for some monks, located many kilometres outside Lyons - which itself is only a provincial city. Yet, the world beat a path to its door. So also Ronchamp a minuscule chapel, in quite an inaccessible location. That was indeed another great lesson for my generation in India: great architecture has nothing to do with the size of the project. Today, when the biggest names in the profession are battling for the largest commissions, it must be quite difficult for students to distinguish quality from quantity - a fundamental principle that even Ayn Rand messed up in the final scene of The Fountainhead.

III

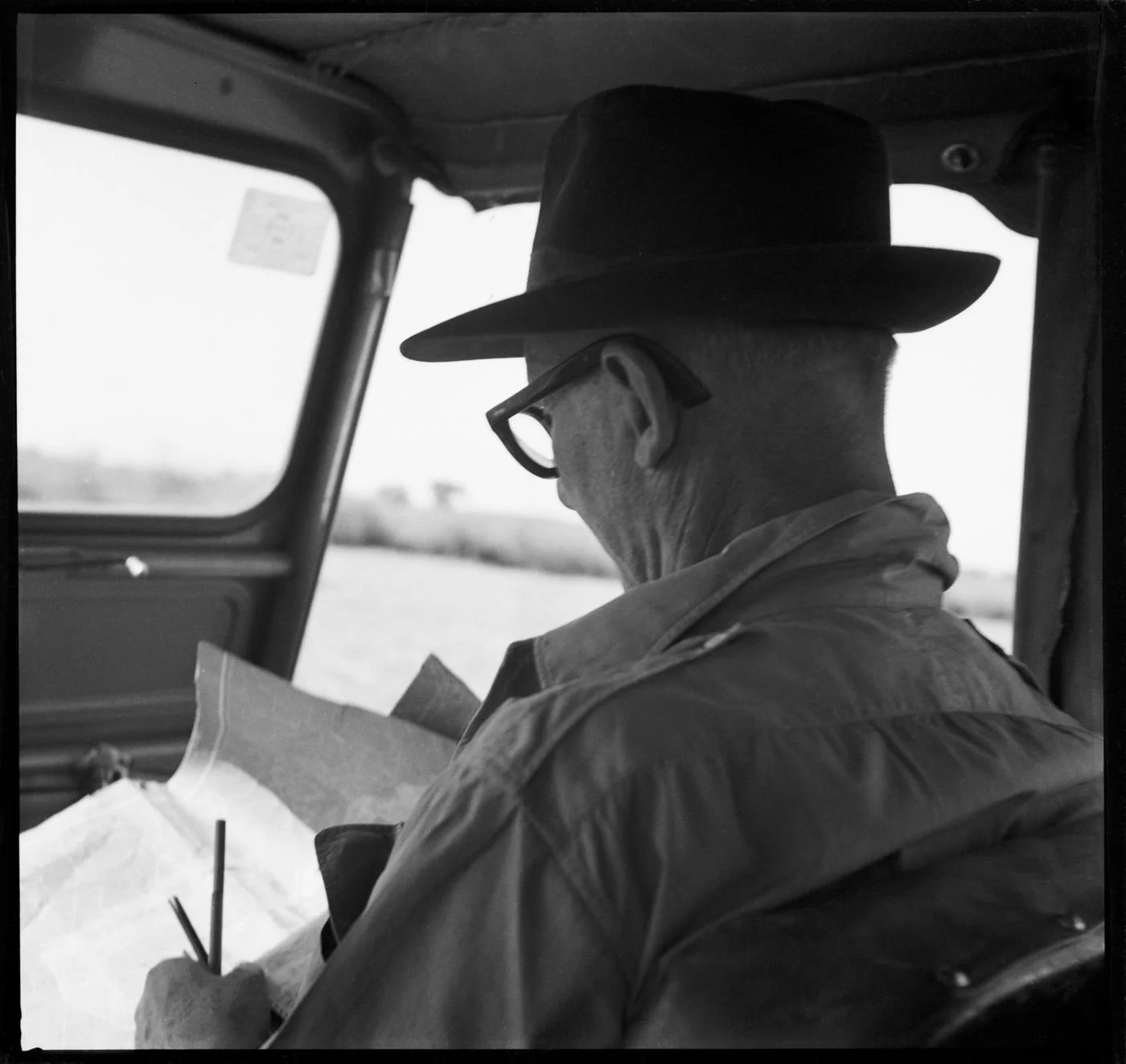

Edwin Lutyens' contract for the design of New Delhi in the 1920s specified that he spend six months every year in India. Thus, for extended periods of time, Lutyens perforce had in-depth exposure to the building materials, the climate and the culture of this country (Unfortunately, his contact with the local population appears to have been minimal-though there was a certain amount of dialogue with British architects already working in India, which supposedly compelled him to examine more closely local craftsmanship and traditions.) For the design and building of Chandigarh, the Government of India decided to take this process further. The creation of Chandigarh would involve young Indian architects, planners and engineers, so that the experiment became a catalyst, a watershed, helping to define the ethos of the new nation.

So Corbusier agreed to come to India twice a year, once in the summer and once in the winter, for visits that lasted a month at a time - this in addition to his colleagues Jeanneret, Fry and Drew, working on full-time government contracts for a period of several years. This arrangement created a special culture in Chandigarh, one in which the Indian architects and engineers could learn a great deal from these foreign colleagues - and the other way round as well! The visitors could profit from the kind of feedback that only local experience and insight can provide.

It is unfortunate that our profession today works under very different conditions. Architects seemingly are forever hopping on airlines, designing a new building almost every time the plane lands. Exposure to the local culture is minimal - something of little relevance.

Our prototype seems to have become the concert pianist -Rubinstein! - flying around the world, playing brilliantly the same Chopin programme, one night in the jungles of Manaus, the next in London, the third in Tokyo. The concert pianist can do this, for his music is a moveable feast. But architecture?

Of course, one should feel free to build anywhere one chooses - but surely it must be in a place that speaks to you. Like Corbusier's journey to Brazil - a visit, back in the 1930s, that really brought him to life. And the same was also true of his experiences in India. To design for a society you understand - and respond to - is essential in creating architecture of any value. This is not a moral proposition, but a pragmatic one. If you design quickly and off the top of your head (and the more gifted you are, the easier it is to do), you do not get any nourishment in the process. The tragedy of our profession today is that so many of the best and brightest are going around the globe. doing just that - and thrashing their own talent.

In this connection I was intrigued to learn that Matisse, whose paintings depict so many exotic locales, could actually put brush to canvas in only three places: Paris, Nice and Morocco. Perhaps it was the special quality of light they possessed - but it could also have been something more compulsive than that. Like the birds that fly thousands of miles every winter from Siberia to sojourn in the marshes around Agra, perhaps Matisse was programmed to paint that way. Artists understand this - because their art is rooted in their sensibilities. And so they refuse to act against their instincts, understanding intuitively that this would destroy them.

IV

Now we come to a different subject: the planning of the city of Chandigarh itself - and here we must perforce change gears. For the city-planning theories that Corbusier brought to the task were woefully inadequate in fact, really quite irrelevant - to the urban issues he had to address here in India.

Perhaps, as Sibyl Moholy-Nagy pointed out, Corb was not an authentic city-planner, but really an architect manqué. The incredible success of his early work in the late 1920s had made him the hero of architects all over the world. The invitations poured in - from exotic places like Brazil, Colombia, Algeria. Corb would travel to these countries and deliver lectures to great acclaim - followed afterwards by dinner with the mayor and the local VIPs. Unfortunately, these forays did not usually end up with any new architectural commissions. Instead, what Corb produced, presumably for the mayor's benefit, was a master plan for the city or at least a conceptual plan, often drawn on the back of the menu card, or on a napkin. By the end of the 30s, he was indeed frustrated. Lacking clients for his architecture, he reinvented himself as a planner of cities.

Picasso said: 'I've always wanted to design a building - tell me, is it very difficult?" To which Corbusier replied: 'No! It's easy! Come to my atelier tomorrow and I will show you how! I love that scene - two world-class, self-taught medicine-men, confident they had the talent to do it all. (Alas, says Corbusier, Picasso never showed up at the atelier.)

Easily said - but how is it done? A few years ago I came across (perhaps in one of Corb's journals?) a very revealing incident that occurred at the opening of an architectural exhibition in Paris, celebrating the completion of the Unite at Marseilles. The CIAM architects were all milling around, lavish in their praise. But what astounded Corbusier was the sudden appearance of Picasso! Now, although Corb saw himself primarily as a painter, no one of this stature had ever deigned to visit one of his painting exhibitions. So he went up to Picasso and they started this extraordinary conversation. Picasso said: 'I've always wanted to design a building - tell me, is it very difficult?" To which Corbusier replied: 'No! It's easy! Come to my atelier tomorrow and I will show you how! I love that scene - two world-class, self-taught medicine-men, confident they had the talent to do it all. (Alas, says Corbusier, Picasso never showed up at the atelier.)

But Corb's confidence is understandable. After all, hadn't he taught himself architecture - and become the most celebrated and influential architect of the century? And rightly so for his natural gifts for architecture were so sensational, he could understand effortlessly what needed to be done. That is to say, he was a great sculptor who understood that architecture is sculpture, but with the gestures of human occupation as an integral part of the abstraction. This is what we see in the work of Alvar Aalto and Frank Lloyd Wright - and also in the great architecture of the past. This is what separates the true architect from the sculptor and the graphic artist. The gestures of human occupation - giving scale and life to the abstraction.

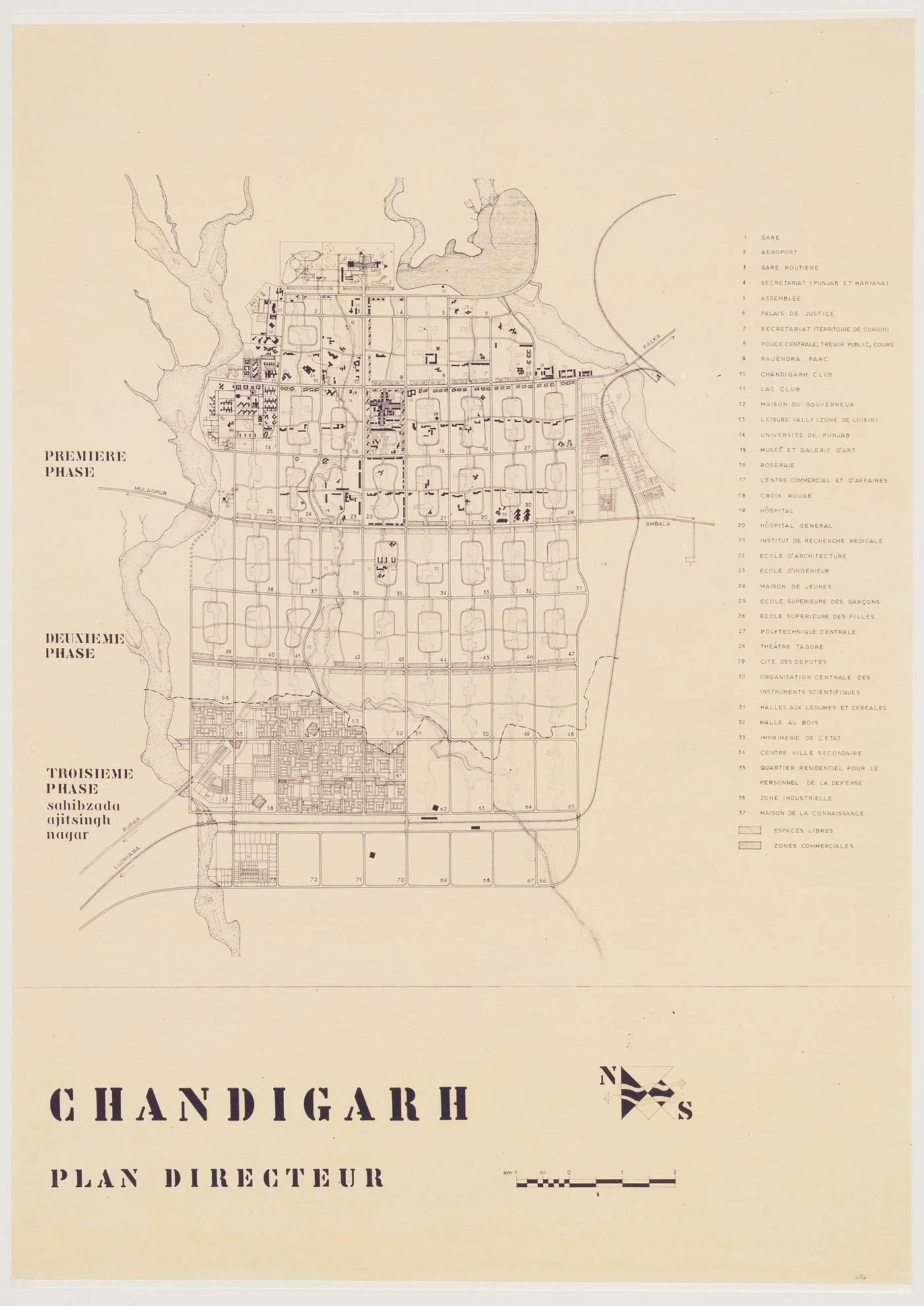

Unfortunately, Corb did not possess the same God-given gifts when it came to city planning - as perhaps he himself finally realized. So when Chandigarh came along, he reverted back to what he understood best: Architecture! For the next few years, he devoted himself to the Capitol complex (always sketched against the foothills of the Himalayas, so that his life comes full cycle back to the paradigm of the Parthenon). The rest of the city he left to the lesser mortals, viz., Jeanneret, Fry and Drew. How else does one explain the ridiculously low densities that prevail, contrary to all Corb's theories on urbanism? Some believe he was overpowered by the Indian bureaucrats who wanted their lawns and their bungalows. (Corbusier overpowered?) And these low-densities are further exacerbated by the very large area of each sector - 800m by 1200m. It is impossible to walk across these sectors - especially in the hot sun. Why did Corb do this? In his planning projects prior to Chandigarh, he had usually made the sectors 400m by 400m. Perhaps someone had told him that for a fast road, traffic lights at every 400m is too short a distance. But having clover leafs at every 800m is even more insane. And then again, organizing these low-density sectors in a grid makes any public transport impossible. (Perhaps in Paris, Corb rode around in taxis?)

Each sector looks like a delightful miniature world, brilliantly interconnected with the rest of the tapestry - east-west through the shopping streets, and north-south through the generous greens.

But when you look at the great iconic drawing of the master plan of Chandigarh that adorned so many architectural and planning offices during that period, you don't sense any of this. Because you get the scale wrong! Each sector looks like a delightful miniature world, brilliantly interconnected with the rest of the tapestry - east-west through the shopping streets, and north-south through the generous greens. Nothing could be further from the truth. Each sector lives in sad isolation, cut off from its neighbours on all four sides by the V.3 roads, and by the high brick walls that run along the periphery. The result is a city of very separate rooms, a zenana city, lacking the interaction - and the synergy - that we love about cities.

Almost fifty years ago, the urban economist Ved Prakash, analysing land use in Chandigarh, demonstrated that the real cross-subsidy in Chandigarh is the poor subsidizing the rich! The bungalows of the judges, ministers and other 'high government officials' are located on humungous chunks of prime land. And though these sites are anywhere from twenty to 200 times the size of those in more humble sectors, they pay exactly the same unit rates for all the various services (water, electricity, telephone, etc.) - although it costs the city a fraction of the price to deliver these services to a sector with a density of a thousand persons per hectare, than it does to one with just ten. And so, right from the start, the cost of housing and basic urban services climbed out of the reach of the poor. Furthermore, as Madhu Sarin reminds us, although squatter colonies started with the arrival of the first construction workers, the master plan never concerned itself with the kind of dehumanized lives they were leading.

Obviously, if Chandigarh was just the city itself, nobody would ever have bothered to go there. It is the buildings of Corbusier that have attracted architects from all over the world. And rightly so. Although more than fifty years of imitation should have irrevocably devalued its architecture, a visit to the Capitol complex is still a stunning experience. For in contrast to the carefully finished concrete of today, the brutal surfaces generate the wallop of the hand-held camera of cinema verite. The three buildings are a revelation. The construction standards of the state PWD are shoddy, and the maintenance even worse - but the architecture triumphs!

This is why it is tragic indeed that the fourth component in this complex, the Governor's Palace, has not yet been built. It is really the jewel of the wholecomposition an expressionistic construct of incredible power and vitality. For while it is possible to design a large house for a VIP, how do you conceive an abode whose very shape and form proclaim: I am a Governor's Palace! This was the genius of Corbusier - to know how to project architecture at that decibel level, with great fluency and rigour. At the Revisiting Chandigarh conference of 2000, we managed to construct a full-scale mock-up in cloth and bamboo of the main façade. It was a revelation - a vivid demonstration of the pivotal role that the Governor's Palace was meant to play in the composition of the Capitol complex, setting up the crucial cross-axis that turns the Capitol complex around to address the city itself - the only building of the four to do so. It also was frustrating to see how affordable its construction would have been - for it is no bigger than the average cinema hall, scores of which are built every year, all over India.

Why then does it not get built? Because the truth is that the people of Chandigarh, especially the elite, do not like Corb's architecture. In fact, they hate the rough concrete, the raw ambience. They are only too happy to find all three buildings have been safely locked away behind barbed-wire fencing, totally cut off from the city. What these elite, (i.e., those living just south of the Capitol complex from Sectors 2 through 19), love about Chandigarh - at least their half of it is their own lifestyle. Large bungalows with extensive lawns, using city water at highly subsidized rates. What they really want to do, of course, is continue the lifestyle that the British created for themselves in their own cantonments - areas from which Indians were barred (except for a few army officers). Since we weren't allowed to live there during the British Raj, most of the new towns and housing layouts we have built since Independence in 1947 are really just our own versions of the British cantonment: individual houses standing on green lawns, nobody walking on the roads, the only person in sight a servant returning from the bazaar.

So we come to the ultimate irony: despite indifference (and often, open hostility) to Corbusier's architecture and ideas, for most of north India's elite the city of Chandigarh has come to symbolize the good life. And Corbusier gets credit - and gratitude for it! Of no concern is the fact that the city pays little heed to the urban theories that Corb himself propounded as dogma. Nor, on the other hand, is any attention paid to the indigenous typologies that have existed for centuries in our towns and cities - like the havelis: multi-storeyed dwellings built around courtyards, in patterns which make wonderful sense not only socially and culturally, but also in terms of climate and coherent urban form. It was precisely these patterns that the British identified with the natives and rejected so vehemently. Which is why they set up their cantonments. Pathetic indeed that we should espouse so enthusiastically what the rulers left behind.

One cannot help but be reminded of George Orwell's matchless fable, 'Animal Farm! As you will recall, the animals in the story are all terrified of the farmer, who lives in a big house, from which he exercises complete control over them. So they decide, with great trepidation, to try and drive him out of the farm and burn his house down. Surprisingly, by the end of the very first chapter itself, the farmer turns tail and bolts. The animals are overjoyed - in fact, are so deliriously happy celebrating that they become too tired to burn down his house that night. So they decide to postpone it till the next morning. The following day when they get up, other events take place, and they postpone the destruction again - until a few days later, some of the animals (I believe it is the pigs) seize occupation of the farmer's house and start controlling all the others. The rest of the animals are confused and horrified. But every time a horse neighs or a donkey brays in protest, the wily pigs (dancing a jig) flash a picture of the farmer's house, and the poor animal is reduced to trembling submission. The new regime is being validated by the imagery of the old.

Now, Edwin Lutyens was specifically instructed to create a new capital that would proclaim to the native population the overwhelming power and glory of the British Empire and the culture it embodied. In fact, he refused to acknowledge the possible relevance of any indigenous architecture, including the masterpieces built by the Mughal emperors - which he described as 'the work of monkeys'. So after our struggle for Independence was over and the British finally left, what did we do? We immediately occupied Lutyen's buildings, i.e., moved right into the Farmer's House, and used its imagery to validate our right to rule-over our own people! And every time a new building is constructed in New Delhi, (and a horse neighs or a cow moos in protest), edicts are issued to comply with the 'Lutyens-Baker style of architecture' - whatever that means. In other words, even when we get the chance to build anew, we want to extend the Farmer's House.

Now, regardless of what you might like about Chandigarh, or what you might abhor, one thing is incontrovertible: it is not the farmer's house. On the contrary, Corb's work opened a door into another landscape. He showed us that we were free to invent our own future. Not by slavishly following his language - but, through his example, finding the courage to discover our own voices.