Le Corbusier in India: The Symbolism of Chandigarh

-William J.R. Curtis

The essay is sourced from the book Le Corbusier: ideas & forms, authored by William J.R. Curtis first published in 1986 by Oxford:Phaidon Publishers. The essay features on pages 188-201.

“Architecture has its public use, public buildings being the ornament of a country: it establishes a nation, draws people and commerce, and makes people love their native country, which passion is the origin of all great actions in a commonwealth.”

It was consistent with the other twists and paradoxes of Le Corbusier's late career that his grandest monumental designs and most complete urban plan should have been realized far from the industrial countries of the West towards which he had directed his architectural gospel. Neither the United States nor France, the most likely candidates, offered the architect a major public building, and the fiasco over the United Nations only confirmed his already well-formed (and well-founded) suspicions of public patronage. By contrast, India-poor, technologically backward, making the first tentative steps after independence, welcomed Le Corbusier with open arms and a wide range of commissions: the urban layout of Chandigarh, four major government buildings including a Parliament and High Court, two museums, and a number of institutional and domestic projects for Ahmedabad (the subject of the next chapter). Only Paris and La Chaux-de-Fonds can show as many Corbusian buildings as these two Indian cities, and the Parliament building at Chandigarh must be counted one of the architect's masterworks.

Family resemblances can be found between the Indian buildings and Le Corbusier's contemporary European projects. There is a similar sculptural weight, and intensity in the use of light and space; natural analogies and cosmic themes underlie imagery, materials like brick and bare concrete are used in a deliberately rough way to evoke archaic and primitivist associations. Façades tend to be highly textured with intervals controlled by the Modulor, and new elements like the deep-cut brise-soleil, the ondulatoire and the aérateur are employed with thick directional piers. But Le Corbusier was not simply exporting a global formula: his usual type-solutions were modified to the limitations of local technology, the strengths of regional handicraft and the demands of a searing climate. He was quick to realize that he was dealing with an old civilization evolving rapidly towards modern democracy yet also trying to rediscover roots after the colonial experience. Glib modernity and the slush of nostalgia were equally to be avoided. The situation demanded largesse, vision and insight into what was relevant in India's spiritual and material past.

If India and Le Corbusier seem right for one another in retrospect, their initial convergence was anything but straightforward.

Chandigarh was born out of the massacres, tragedies and hopes that attended partition and the creation of Pakistan. In July 1947 the Independence Bill was signed and British rule in India came to an end. When Pakistan came into existence the following year the State of the Punjab was cut in two, millions of refugees fled in both directions, blood was spilt in great quantities and the old state capital of Lahore was left on the Pakistani side. Temporarily business was run from Simla, the British hill station, but this was practically and symbolically inadequate. It was obvious that a new city must be founded to anchor the situation and to give refugees (many of whom were Hindu or Sikh) a home. P.L. Varma, Chief Engineer of the Punjab, and P.N. Thapar, State Administrator of Public Works, considered a number of sites before settling on a place between two river valleys, just off the main Delhi to Simla line, a safe distance from Pakistan and at a point where the huge plains began to fold into the foothills of the Himalayas. Transport, water, raw materials, central position in the state were all practical considerations, but Varma still insists that an intuition of the genius loci played its part. The place felt auspicious: they chose the name after 'Chandi', the Hindu goddess of power.

From the outset it was clear that Chandigarh would be no mere local venture. Pandit Nehru and the central government felt the Punjab disaster keenly and realized the importance of cementing new institutions and housing in place. New Delhi agreed to cover one third of the initial costs and Nehru himself recommended Albert Mayer, an American planner whose acquaintance he had made during the war, to lay out the new city. Matthew Nowicki, a capable young architect who had once worked with Le Corbusier, was selected to concentrate on architectural matters, including the design of the main democratic institutions on the Capitol. A modern and efficient city, with up-to-date services, sewerage and transport was envisaged by the government. Nehru spoke of clean, open spaces liberating Indians from the tyranny of the overcrowded and filthy cities, as well as from the confines of agricultural, village life. Chandigarh, then, was to be a visible and persuasive instrument of national economic and social development, consonant with Nehru's belief that the country must indus-trialize or perish. It was to be a showpiece of liberal and enlightened patronage, and he would later eulogize Chandigarh as a ‘temple of the New India’.

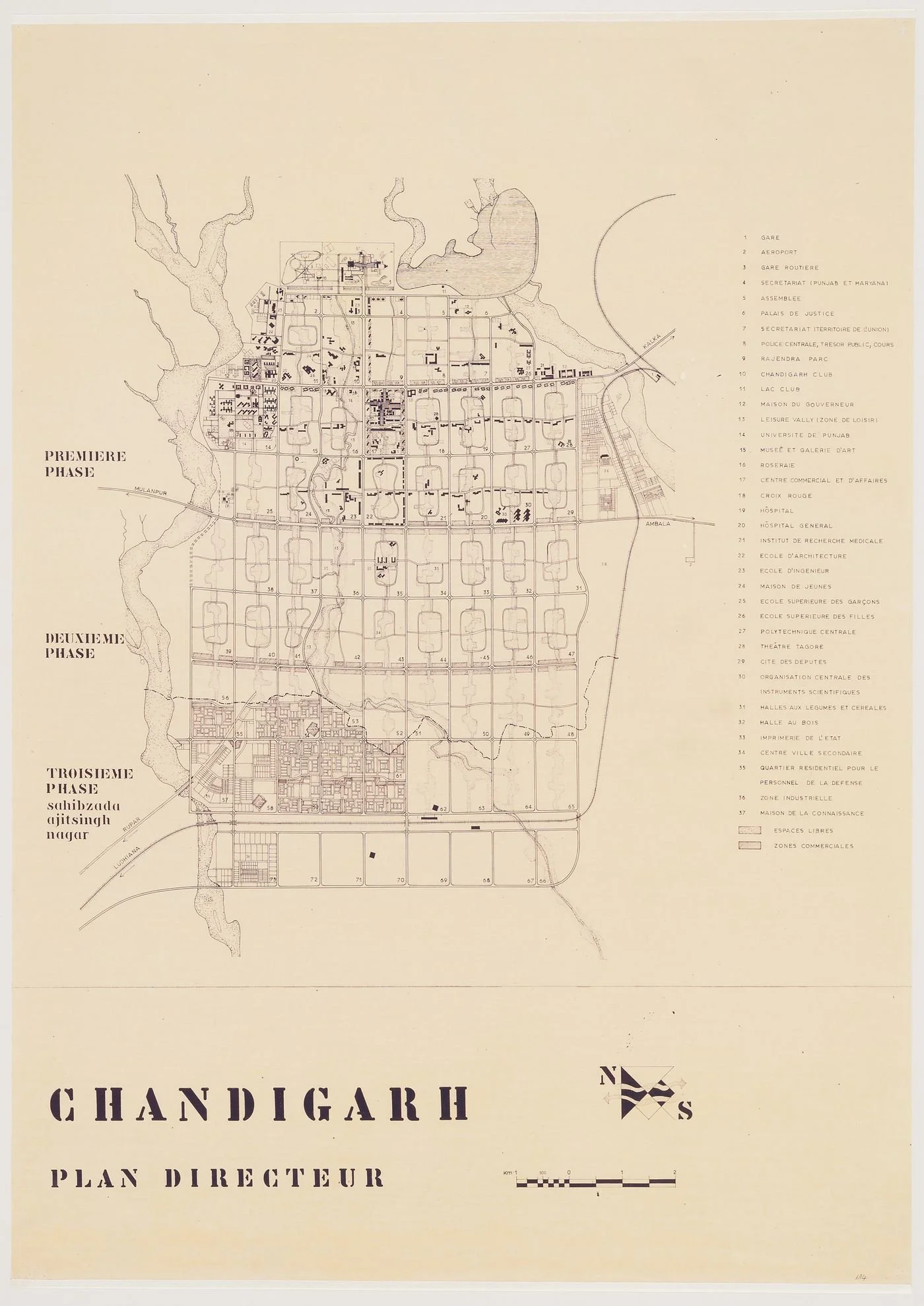

Mayer's plan of 1950 organized the city into sectors around a hierarchy of green swards and curved roads. The commercial zone was at the centre, the industrial area to the south-east, and the Capitol to the top or north-easterly extremity, separate from the residences and on the verge of open countryside. Nowicki's few extant sketches show that he thought of the Capitol as a series of objects separated by wide, open spaces. He began to experiment with a vocabulary of columns and screens for some of the buildings. The Parliament was expressed as a spiral ziggurat, obviously but skilfully modelled on Le Corbusier's Mundaneum project of 1929, Mayer was a major proponent of Garden City thinking in America, and his picturesque roads and green spaces set about with low-rise buildings conformed to this point of view, as well as extending the British tradition of suburban residential zones on the outskirts of numerous Indian towns. But the overall shape of Mayer's plan, as well as the placing of the city of affairs as a separate "head", also loosely recalls Le Corbusier's Ville Radieuse.

Fate intervened in spring 1950 when Nowicki was killed in a plane crash in Egypt. Again Thapar and Varma set out to find a new chief architect. They continued to feel that there was no one in India remotely capable of handling such a thing (scarcely surprising given the habits of professional training under the Raj). They went to London and spoke to Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, who had experience designing in the tropics but who hesitated to take the whole job on and recommended Le Corbusier. The delegation went to Paris and the master turned them down, especially when he heard that they wanted him to move to India and realized how low the fees would be. But gradually he came round, declaring that the necessary work could be done mainly in Paris. Finally he agreed to be chief architectural consultant for the city as a whole and exclusive designer of the Capitol buildings. He accepted a modest monthly salary and agreed to make two month-long visits a year to India. Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry were to be employed on three-year contracts, concentrating attention on the design of all facilities for residential sectors, and then forming teams of young Indian architects to carry on the work (eventually under Pierre Jeanneret). Poor Mayer was to continue as planner, but he would be no match for the far more powerful personality of Le Corbusier, a man who had reflected on the nature of cities for forty years, who saw no real division between the functions of architect and planner, and who now firmly intended to lay down the law.

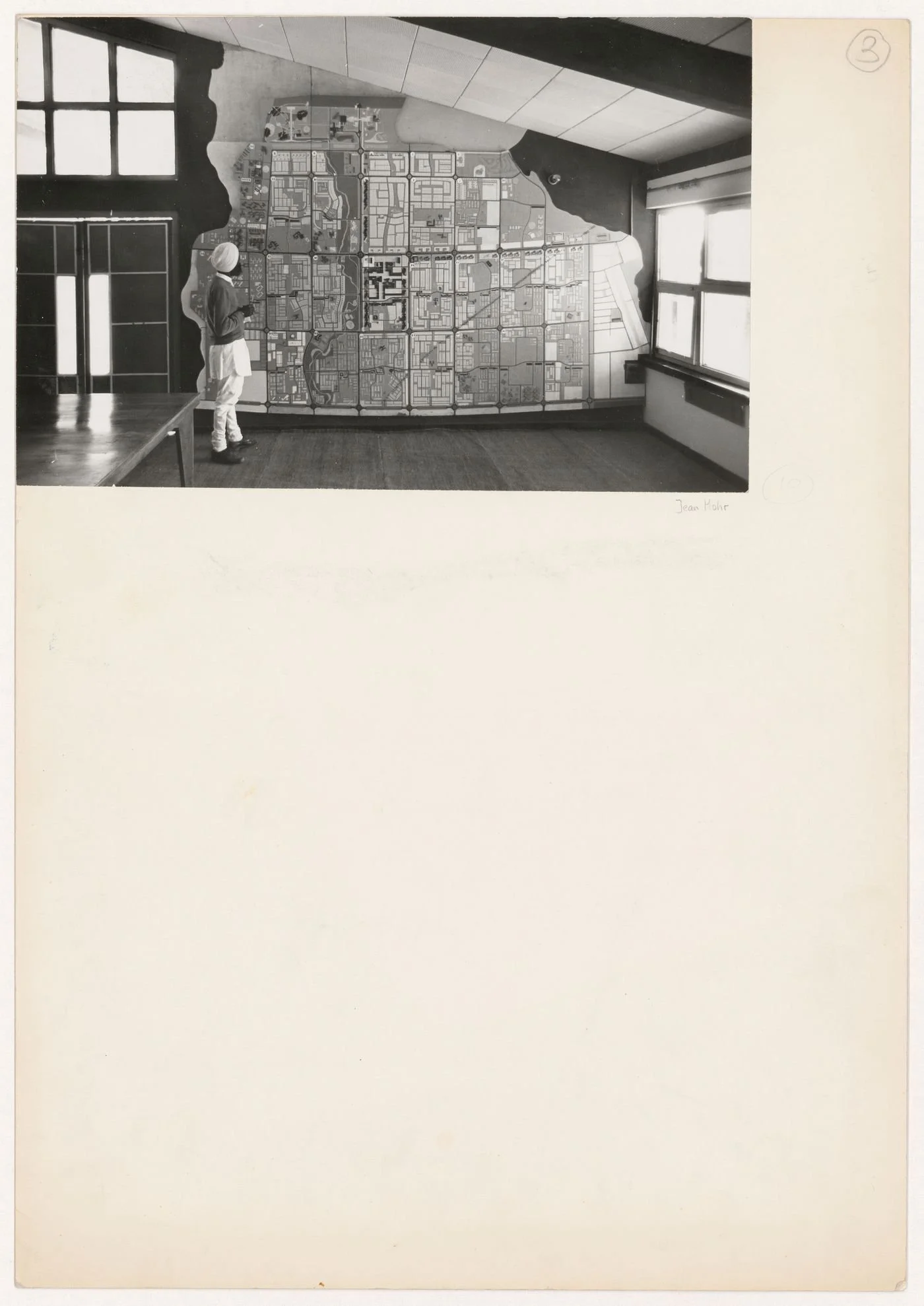

In spring 1951 Le Corbusier went to India and met the rest of the team in a rest-house on the road to Simla, where they worked together for about four weeks. But the guiding principles of the new Chandigarh plan were laid down in four days. In principle it followed Mayer's, as the contract had suggested that it should. But both Fry and Le Corbusier had found the curved roads flaccid, so Le Corbusier returned to an orthogonal grid while Fry sneaked in a few curved lateral roads for variety. The anthropomorphic diagram-head, body, arms, spine, stomach, etc. of the new plan was accentuated by major axial routes crossing towards the centre; it reverted more closely to the form of the Ville Radieuse. But the elements making it up were quite different. The skyscrapers of the technocrats were replaced by the shelters of democracy at the head; the communal medium-rise apartment houses of the main body were replaced by a gradation of different house types (eventually fourteen in all) catering for manual labourers at the bottom social rung up to judges and high-level bureaucrats at the top. There would be variants on terrace houses and magnificent modern bungalows but (it was eventually decided) no high-rise buildings. Le Corbusier realized that his usual housing models had a limited relevance in a place where there was plenty of land and where people were used to living half outside. He confided to his sketchbook that the basic unit in the Indian city was the ‘bed under the stars’.

Each rectangular sector of Chandigarh measured about 4,000 by 2,600 feet and was to be regarded as a largely self-contained urban community.

Sectors were linked and separated by a grid of different sized roads varying in size from small bridle (or rather bicycle) paths within the sectors, to residential arteries, throughways, and finally the grandiose Jan Marg running up the centre of the city towards the Capitol. In all seven main types of circulation were worked out; typically these were canonized 'les sept Vs' (short for 'voies' or 'ways'). Evidently Le Corbusier was anticipating a time when motor traffic might become a major force in India. In other respects too the plan followed old Corbusian prescriptions, the separate zoning of living. working, circulation and leisure; the fusion of country and city through the planting and provision of trees and parks; rigid geometrical control and delight in grand vistas and processional axes; a sense of openness rather than of enclosure; a lingering hope that urban order might bring social regeneration in its wake.

Much of this runs against the planning fashion of the moment, which is squeamish about any form of environmental determinism, nervous about the grand plan, and committed to spatial enclosure and the cultivation of visual variety. But before the dictates of the present are imposed on Chandigarh it should be born in mind that a bold statement of order embodying the idea of a beneficent but stabilizing state was a virtual demand of Le Corbusier's clients. The elite with which he had contact was cosmopolitan and often Western-educated; it probably did not see itself living in some higgledy-piggledy Orientalist version of Indian Life'. Le Corbusier's mandate came in part from Nehru, who later spoke of Chandigarh as 'reaching beyond the existing encumbrances of old towns and old traditions' and as 'the first large expression of our creative genius, founded on our newly earned freedom’. There was little room in this vision for Gandhi's spinning-wheels or for his idealization of the village as the moral core of Indian life: indeed the construction of Chandigarh entailed the destruction of a number of villages.

Of course there is no divine rule which says that grids and axes are the only appropriate metaphors for the rational and modernizing powers of government, but in Le Corbusier's mind such associations probably did exist. It was as if he wished to give to the New India its symbolic equivalent to the Raj's New Delhi. He studied and admired the grand axes and main Raj Path of that city, as well as the monumental approach to Lutyens's Viceroy's House, Like his English predecessor he too hoped to synthesize the Grand Classical and Indian traditions with a statement of modern aspirations. But obviously the task of crystallizing the ethos of a liberated and democratic society was quite different from that of expressing foreign domination and imperial power. Le Corbusier's belief that the city as a whole should carry symbolic values took him back to old fascinations: the axis between the Arc de Triomphe and the Louvre; the superb iconographic clarity of the plan of ancient Peking: perhaps even to the ancient Hindu theoretical texts on urbanism, the 'Shilpas' in which cities were sometimes described as centric diagrams with main roads intersecting at their centre. It is rather doubtful whether Le Corbusier studied these theoretical precepts, but he certainly knew a relatively modern incorporation of them: the early eighteenth-century city of Jaipur, which was laid out on a grid of wide streets. If Le Corbusier had taken a greater interest in the urban qualities of the commercial centre at Chandigarh he might have found relevant lessons at Jaipur for the shaded linkage of public courtyards; unfortunately he did not.

Gandhi crept into his musings through the back door as he revelled in village folklore and the apparent harmony of people, things, animals and nature.

Thus, despite the rhetoric of Nehru, the past was not banished at Chandigarh; rather it was examined critically for relevant lessons of organization. The housing by Fry, Drew and Pierre Jeanneret used concrete, brick and modern plumbing and equipment, but the architects also tried to respect custom and caste in the house plans and to transform vernacular prototypes in the provision of loggias, sleeping terraces, territorial walls and shading. Le Corbusier's Indian sketchbooks brim over with rustic enthusiasms. He sketched the simple yet ancient tools of the peasants, returning time and again to the robust forms of bull-carts. Gandhi crept into his musings through the back door as he revelled in village folklore and the apparent harmony of people, things, animals and nature. Thus the sophisticated foreign primitivist intuited links between his own contrived pantheism and the deeply rooted cosmic myths of India's ancient religions: the 'delights of Hindu philosophy', the 'fraternity between cosmos and living beings'. And all this seemed substantial, rich and vital alongside the anaemic and trivial values of modern industrial life. Gradually India settled into Le Corbusier's mind as a country that must avoid the voracious industrialism of the "first machine age' by forging a new culture on a firm moral base involving equilibrium between the religious and the secular, the rustic and the mechanical.

While Le Corbusier was absorbing the human content of the Chandigarh problem he was also reflecting on the best ways of dealing with monsoons and extreme heat. He studied or sketched vernacular structures, colonial verandas, the loggias of Mogul pavilions, the shaded walk-ways of Hindu temple precincts, and tried to distil the basic lessons from them. These in turn he sought to blend with the fundamentals of his own architectural system: the skeleton of the Domino or the low vaults of the Monol. In his search for a basic, modern 'Indian grammar the North African projects from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s were obviously pertinent, especially for dealing with the sun.

Le Corbusier's guiding ideas for the Governor's Palace, the High Court, the Parliament and the Secretariat developed with astonishing rapidity in his portable atelier, the sketchbooks. The unifying theme and leitmotiv of the Capitol was established as the parasol or protective, over-hanging roof, supported on either arches, piers or pilotis. This device would shelter the buildings from sun and rain while remaining open at the edges to catch the cool breezes and allow a variety of views. The parasol was also capable of a multiplicity of meanings, and Le Corbusier soon discovered poetic and cosmic possibilities in sketches which showed water sluicing off roofs into basins. The idea could in turn be modified to create loggias, verandas, scoops, porticoes, and curved or rectangular roofs hovering above deep undercrofts of shadow. Brise-soleil screens of various kinds could be suspended, attached or built up in front, generating openings and entries or allowing the eye to penetrate to the depths of buildings or even beyond them to mountains and sky. Le Corbusier was to discover that the parasol could also resonate across time, recalling a number of symbolic motifs in the history of Indian architecture.

Among Le Corbusier’s earliest Indian sketches were ones of the eighteenth century garden at Pinjore that used clever effects of illusion to compress together terraces of water with the rugged outlines of the landscape.

Le Corbusier placed the Governor's Palace at the head of the Capitol, and the Parliament and High Court lower in the hierarchy facing one another but slipped slightly off each other's axis; they flanked the view to the Palace and expressed the idea of a balance of powers between the judiciary and the executive. The Secretariat was lodged behind and to one side of the huge hieratic box of the Parliament. It was as if Le Corbusier had re-adapted the devices for distinguishing ceremonial from workaday aspects of government from his League of Nations scheme years before, but exploded them across a huge platform. Throughout its evolution the plan of the Capitol bore comparison with the rectangles and flanges in tension of an early Mondrian or else with the sliding objects and subtle axial shifts of a Mogul palace or garden. Among Le Corbusier’s earliest Indian sketches were ones of the eighteenth-century garden at Pinjore that used clever effects of illusion to compress together terraces of water with the rugged outlines of the landscape. As his ideas for the spaces between the monuments developed he incorporated hillocks, trenches for vehicular circulation, water basins, ramps and (eventually) a panoply of signs and symbols illustrating the philosophy behind the city. These were all orchestrated into a surreal landscape in which foreground and back-ground were ingeniously compressed to produce bizarre illusions of size and scale.

While Le Corbusier was weighing up the over-all shape of the Capitol he was also trying to establish appropriate forms and symbols for each institution, always on the basic theme of the parasol. A variant emerged in the project for the Governor's Palace (1951-4), eventually not built because Nehru found it undemocratic. It would have dominated the site from afar with its intricate silhouette standing out against the blue haze of the hills. It was preceded by ramps, pools and sunken gardens, and approached off-axis by car along a valley route; a similar means of access was worked out for all the buildings. The image was dominated by the upturned crescent on top. This was lifted up on four supports, creating a small theatre for nocturnal events above and a shelter for afternoon receptions underneath. The shape seemed to gesture up towards the planetary realm and would have answered similar shapes in the neighbouring constructions. Many images were compressed into it. Among Le Corbusier's travel sketches are some comparing bulls horns to tilted roof structures open at the edges to let air pass. The bull was related to old animist themes in Le Corbusier's paintings (stemming ultimately from the Surrealist obsession with Minotaurs) as well as perhaps to Hindu iconography since Nandi the bull was a vehicle of Shiva; in this case, surely, the image also had to do with Le Corbusier's nebulous belief that India's future lay in a fusion of traditional rural values and modern progressive ones in another part of the Governor's Palace a curious sculpture was proposed which blended the bulls' horns with an aeroplane propeller. But the parasol was in turn an ancient symbol of state authority, found on top of Buddhist stupas and in a much later domical or arched form in Islamic monuments. The Governor's Palace, portrayed at the end of its pathways and pools, silhouetted dramatically against the sky, experienced both frontally and in torsion with its surroundings, recaptures some-thing of the spirit of the Diwan-I-Khas at Fathepur Sikri, a site that the architect had seen and admired. In this example, chattris or domical variants on the parasol were lifted at the four corners of the roofline on slender supports through which the sky could be seen.

Le Corbusier was certainly aware of a much later attempt at a 'beneficent imperial eclecticism: that of Lutyens in the Viceroy's House in New Delhi. The main dome of this building declared the power and tolerance of the Raj through the fusion of stupa and Classical dome, rather as the city layout declared respect for the past by careful alignments with the various ancient Delhi. The imperial hat was then impishly turned on its head in other parts of the building to become a scoop or water basin; in the gardens at the back a pretty Edwardian version of Mogul landscaping continued the aquatic theme. But the dome would not have been an appropriate emblem for Chandigarh even if Le Corbusier had not regarded the form as defunct. So it was transformed into a counter-shape, a form that did not compress its forces downwards, but that sprang upwards, open and free. This was the emblem for the new, democratic, liberal and liberated India - a shape that echoed the gesture of the 'Open Hand', Le Corbusier's symbol of international peace, transcending politics, caste, religion, race. It was the very symbol that he hoped to erect adjacent to the Governor's Palace where the two silhouettes could be appreciated simultaneously. In transforming certain buildings within the Indian tradition it was not the architect's aim to make obvious references to particular creeds and periods but to create a truly pluralist imagery touching on universal human themes. The foreign and the indigenous, the new and the old were in this case blended into an imagery for the new Indian identity around pan-cultural ideals that were the opposite of tyrannical.

Variations on the sheltering roof idea were used in the other buildings as well. The High Court, for example, was conceived as a huge open-sided box under a giant roof standing on a 'grand order' of concrete piers. These formed a portico marking the asymmetrical entrance where they were slightly curved in plan recalling the subtleties of the Pavillon Suisse pilotis or the heroic supports under the Marseilles Unité. The Supreme Court was to the left of the entrance on its own, while the other courts spread out to the right under the parasol behind a secondary system of sun-shading grilles. Massive ramps zigzagged their way laterally through the structure linking to upper-level offices and offering vignettes of the Parliament in the distance between the piers (eventually the three supports at the entrance were painted red, yellow and green). The under-side of the parasol was arched in a manner recalling sketches that Le Corbusier had done forty years earlier of the Basilica of Constantine. The huge parasol was intended to convey the 'shelter. majesty and power of the law'. Under the entrance Le Corbusier placed an odd little sculpture of a snake rising from a water basin: his own curious interpretation of a coiled serpent embodying the principle of spiritual power.

Le Corbusier's dabblings in cosmology and researches into tradition would have been all for nought if he had not had the means to transform ideas into sculptural forms of prodigious force and presence. From the start he thought in terms of concrete. The material was far from perfect for high temperatures but local know-how and materials did exist. Construction would be labour-intensive, and over the years the 'prophet of the machine age would be treated to the sight of hundreds of Indians swarming over wooden scaffolding tied with ropes, or wheeling tiny loads of concrete up rickety ramps before packing the stuff into place between rough planks. The resulting crudities were turned into richnesses in the creation of an instant patina that gave the buildings an archaic feeling appropriate to Le Corbusier's intentions. If the rude and powerful shapes recall Marseilles and La Tourette they have equally to be seen in terms of the indigenous mud architecture which the architect admired close to Chandigarh. It was typical of him that he should have sought to combine the vitality of folk craft with the abstract fastnesses of courtly monumental traditions. Concrete allowed him to sculpt with broad ochre surfaces gashed by openings of shadow. In the bold creative moves made in sketches between 1951 and 1953 a new language of monumentality was invented that went well beyond the spindly limitations of the International Style but without regressing into ersatz historicism. The finished Chandigarh monuments have the air of buildings that have stood there for centuries: an architecture 'time-less but of its time’ (Pls. 151-4).

Le Corbusier was on the alert for ritual. He wished to give shape to the dominant role of the Assembly Chamber and to the dialogue between it and the Senate.

The High Court was the first structure to be erected on the Capitol and so served as a trial in the realization of ideas. In parallel Le Corbusier evolved the most complex of the designs, that for the Parliament. This began life as a large, inward-turning, shaded box preceded by monumental arches and by an even larger arched portico. Ancient Roman sources again come to mind (the Pont du Gard, the basilicas), but gradually the idea was simplified towards a trabeated solution with the sides behind brises-soleil and the front facing the plaza as a scooped portico. This appeared to gesture across the Capitol and also acted as a huge gutter to sluice the monsoons. The plan extended an old Corbusian pattern: a free-plan grid of supports with the main functional organs set down into it as curves. Le Corbusier was on the alert for ritual. He wished to give shape to the dominant role of the Assembly Chamber and to the dialogue between it and the Senate. Public involvement might be implied through surrounding forums in the hypostyle and through the portico linked to the setting as a sort of shaded stoa.

As at Ronchamp and La Tourette, Le Corbusier explored the mythical qualities of light and darkness in the Parliament Building. Early sketches showed rays of sunlight and moonlight penetrating the interiors in a dramatic way; there were even obscure references to 'nocturnal festivals'. As problems of lighting and ventilating the Assembly Chamber came to the fore, the architect broke the room up through the roof as a tower (Pl.3). In one version he added a spiral walkway as a stair for the window cleaners, but this surely had a symbolic role too. The spiral suggested growth and aspiration, and perhaps echoed Tatlin's Monument to the Third International (1919) or various revered minarets in the history of architecture (e.g. Samarra, Ibn Tulun). Later the tower was modified to take on a hyperboloid geometry inspired by cooling towers that Le Corbusier saw in Ahmedabad.

To observe the design process of the Parliament is to see customary elements of the architect's vocabulary invested with fresh levels of meaning. The reference to a cooling tower might be seen as an appropriate image for Nehru's policies of modernization and industrialization, but these twentieth-century myths were blended with ancient sacral images. In some of his sketches Le Corbusier compared the Assembly space to the dome of Hagia Sophia with rays of light streaming down. Celestial connotations in his rethought dome were reinforced by the idea of having a single ray of light hit a column of Ashoka (the first Emperor of India) on the Speaker's rostrum on the occasion of the annual opening of the Parliament. The axis of the room was aligned to the cardinal points, and so twisted from the geometry of both building and city. These solar gestures were supposed to remind man that he is ‘a son of the sun’. There is an echo of the Pantheon- a microcosm linked through its oculus to the planetary order - but the idea of a ray of light bringing its renewing power to the darkness and touching a shaft of stone is also found in Hindu temples. In the Parliament the path through the main ceremonial door (with its various solar diagrams) takes one through a zone of transition into a hall of columns and then around the base of the Assembly funnel in a clockwise direction recalling ritual circumambulation in ancient Indian religious architecture. One other association may have floated into Le Corbusier's memory in his search for an appropriate image of congregation: the funnel-like chimneys of Jura farmhouses of his youth, into which the whole family would climb. Through a prodigious feat of abstraction old and new were compressed together in a single symbolic form (Pls. 151, 152).

“The astronomical instruments of Delhi... They point the way: relink men to the cosmos... Exact adaptation of forms and organisms to the sun, to the rains, to the air etc. this buries Vignola...”

A similar procedure of analogy and transformation is sensed in the design of the top of the funnel with its tilted plaque, its up-turned crescent and its downward-turning curves. Le Corbusier let it be known that he wanted the top to be equipped for 'the play of lights', that he was thinking of it as a sort of observatory. This suggests that he may have been inspired by the extraordinary abstract constructions at the Jantar Mantar in Delhi which had prompted him to exclaim in his sketchbook: "The astronomical instruments of Delhi... They point the way: relink men to the cosmos... Exact adaptation of forms and organisms to the sun, to the rains, to the air etc. this buries Vignola...” Planetary crescent paths can be found traced in stone in these prototypes, and Le Corbusier's studies for reliefs, enamels, tapestries and monumental signs indicate that he was fascinated by the curves of the sun at solstice and equinox. The crescent curve undergoes metamorphosis: it echoes the Open Hand, the Governor's Palace silhouette. bulls horns, the chassis to carry the planets in their cycles. Time and again in the sketchbooks he returns to the form of the bull-cart wheel with crescent-shaped suspension resting on the hub. Like the parasol, the wheel was an ancient image of complex religious and political meaning that did indeed touch on cosmic and solar themes; it was also a modern Indian Nationalist symbol.

The plan of the Parliament is an ideogram rich in intentions. It seems to be modelled on that of the Altes Museum in Berlin by Schinkel; at least both are variants on a fundamental type where a stoa or portico precedes transition towards a domical space and where the hierarchy between ceremonial spaces and more mundane functions at the fringes (at Chandigarh the offices) is clearly marked. But Le Corbusier rejects Neo-Classical symmetry in favour of a turbulent contrast between symmetry and asymmetry, rectangular and curved, funnel and pyramid, box and grid. The roof volumes mark the main chambers and enter a spatial dialogue that reaches out to mountains and sky. Within they battle with the grid, compressing space in a way inconceivable without the plastic intensity of Cubism. The day-to-day entrance is to the Secretariat side, two levels below plaza level (a valley allows these buildings extra accommodation downwards). The ramps slice back and forth in section, allowing diagonal views of the funnel descending into the hypostyle, whose concrete mushroom columns are lit soberly from mysterious side sources. One enters the main chamber and the space expands upwards but in a manner that does not detract from the function and focus of the room.

The portico of the Parliament blends the crescent themes with the functions of sluice and frontispiece. Once again the gestural action of this shape reveals its capacity to lunge over great distances, in this case towards the High Court 400 yards away. Seen obliquely, it points to the mountains. Head-on, the turbulence ceases and it becomes a wide, low horizontal. Like Ronchamp, the Parliament is a sculpture in the round that emits entirely different sensations from different points of view. The frontal approach suggests less a Classical portico than a Mogul audience chamber of the sort that Le Corbusier had observed in the Red Forts of both Delhi and Agra. These were defined by grids of supports open at the edges for cross-ventilation and shaded from sun and rain by deep overhangs. Le Corbu-sier's solution responded to analogous issues with equal formality but in the terminology of his new 'Indian grammar'. He bridged the gap between East and West, ancient and modern, by seeking out correspondences of principle.

For the Chandigarh Secretariat Le Corbusier originally intended a skyscraper. In its second version this was like the tower he had suggested for Algiers-textured with deep crates of brise-soleil which also functioned as balconies; the recently rejected United Nations Secretariat would have employed a similar system. But despite the architect's eagerness to demonstrate at last the 'correct' form for the skyscraper it gradually became clear that this was not the right place as a tall building would have dwarfed the ceremonial buildings. So the block was put on its side where it could act as a terminating barrier to the Capitol and as a backdrop to the Parliament.

Even then its sheer bulk had to be lessened by lowering the ground level through excavation The resulting slab was nearly 800 feet long and contained eight sub-units. The construction joints between them were hidden behind a continuous screen of brises-soleil. The Modulor and the recent experience of Marseilles were both a help in balancing unity and variety, monumentality and the human scale. The fourth sub-block was varied in its façade treatment and amplified in its apertures to express the presence of the ministerial offices. The full fenestration system comprised ondulatoires, aérateurs with insect screens as well as the brise-soleil fins. Movement of air was encouraged by fans, but air-conditioning was considered too expensive. Besides, Le Corbusier probably wished to demonstrate his natural devices for dealing with the climate. In truth these have been only partly successful. This enormous office building had to deal with the daily shifts of a huge labour force. Lifts and stairs were complemented by curved ramps sticking out from the slab like ears or handles. There was also a roof terrace affording sheltered places from which to enjoy the long views over landscape, city and Capitol.

It was Jane Drew who initially suggested to Le Corbusier that he should set up a row of signs symbolizing his architectural and urbanistic philosophy: the harmonic spiral, the signs of the Modulor, the S shape signifying the 24-hour rise and fall of the sun, curves showing the path of the sun at equinox and solstice and, of course, the Open Hand rising above the curious 'valley of contemplation'. In addition Le Corbusier envisaged a curious sculpture of a broken Classical column with a tiger advancing upon it: an image of the collapse of British rule and the reassertion of Indian identity. When the Governor's Palace was rejected, Le Corbusier decided to replace it with a 'Museum of Knowledge'; later still he conceived a Tower of Shadows' to stand between Parliament and Justice- his twentieth-century version of the Jantar Mantar for registering sun angles on different-sized brises-soleil. At the time of writing, this last contraption and the Open Hand are in the process of construction, so the Capitol is in essential ways incomplete. But similar signs adorn both the boldly coloured tapestries that Le Corbusier designed for the High Court and the large enamel ceremonial door under the portico of the Parliament.

Intended as a popular art, the signs come very close to magniloquent kitsch. The reverent see in the Open Hand a pan-cultural significance, a cross between a Buddhist gesture for dispelling fear and a hovering Picasso Peace Dove. The cynics see a grotesque baseball glove and 'the fiction of a state art with no state religion behind it’. But Le Corbusier took it very seriously as an emblem of universal harmony representing, among other things, the belief that India might lead a moral regeneration. The form had a most complex genesis perhaps going back as far as the Ruskinian moral symbolism attached to fir trees in his youth. Le Corbusier is reported to have described the Open Hand as: a plastic gesture charged with a profoundly human content.

A symbol very appropriate to the new situation of a liberated and independent earth. A gesture which appeals to fraternal collaboration and solidarity between all men and all the nations of the world.

Also a sculptural gesture... capable of capturing the sky and engaging the earth.

By the late 1950s there was enough above ground at Chandigarh for Le Corbusier and the world architectural press to begin to judge what the finished buildings might look like. Along with the other late works they played their part in encouraging a reaction against the steel and glass clichés of the previous decade: in the 1960s bold concrete porticoes and piers became standard fare in city halls and cultural centres in many parts of the world. Meanwhile Le Corbusier turned to smaller buildings in Chandigarh such as the Museum and Yacht Club (Pls. 156, 158). The former was a red-brick box lifted up on pilotis and top-lit through light troughs. Ramps rose to one side of the double height lobby, guiding the visitor through the exhibition sequence. The building was a close relative of the museums for Ahmedabad and Tokyo. Like them it descended from the Museum of Unlimited Growth of the 1930s. At Chandigarh slight refinements such as the alternating system of piers and oval pilotis (creating bays and a free plan simultaneously) were enhanced by sober lighting and tight proportional control. The Yacht Club was even simpler, being a distillation of the "Indian grammar' into a delicate, concrete-framed pavilion with free-plan partitions playing against the grid. The site was to one end of the lake that P.L. Varma insisted be built.

With its long, wide esplanade, its views to the mountains and its glimpses of the distant silhouettes on the Capitol, this must be counted among the most beautiful spots in Chandigarh.

It is still too early to come to conclusions about the urban qualities of Chandigarh: for most criticisms there is an answer. If one side claims that it is an ill-begotten toy of neo-colonialism another replies that it is the benchmark by which later Indian planning must be judged; for someone who points to uniformity and rigidity someone else can be found to point to the shaded streets of the better-off sectors or to the splendid views of the mountains: the moan that the streets are too wide is countered with the observation that Chandigarh is easily able to absorb its growing traffic; vague charges of being 'un-Indian' are met with the reminder that the place offers welcome relief from the filth and overcrowding of the traditional population centres. There is almost universal agreement that Le Corbusier's principle of discrete zoning is singularly ill-matched to the complex mixed uses and mixed economies of Indian life, and almost universal condemnation of the vapid, sun-baked spaces of the commercial centre in sector 17. What was intended to be a modern version of a 'chowk' or bazaar area has come out as a bleak no man's land flanked by dead-pan rows of pilotis and brutally proportioned balconies. It seems odd that Le Corbusier should not have devoted time to the 'stomach of his anthropomorphic city; Fry was shocked to return later and discover how bleakly these spaces had turned out.

Whatever its faults, the extraordinary thing is that Chandigarh exists at all: the expression of a huge collective effort that was launched after strife and tragedy.

In its early years of growth the city has far outstripped the initial figure of 150,000 to approach the intended final population of half a million. It has played a central role in the economic transformation of the Punjab into one of the richest areas of India, a process achieved partly through industrialization and the mechanization of farming. This success brings problems in its wake. If the city goes on expanding as an industrial centre there is the danger that its positive qualities will be undermined by speculation, bureaucratic graft and laissez-faire construction. The growth has also had its political stresses. In 1966 the Punjab was again divided. and the new state of Haryana now occupies half of the Parliament Building. At the time of writing Sikh aspirations towards independence are stimulating unrest in the Punjab with the threat of further divisions. As the idea of a pluralist, secular state takes increasing buffeting from various religious extremisms, the Open Hand still lies in prefabricated fragments, rusting in the grass, its messages dimly heard.

Le Corbusier's 'Indian grammar' has not always been a success in others' hands, and at Chandigarh the vocabulary has been spread very thin. Yet the master's work and presence have founded a modern Indian tradition of real worth, containing architects of calibre like Balkrishna Doshi, Charles Correa and Raj Rewal. To them, and to an even younger generation, Chandigarh is a bold beginning whose lessons need transforming still further to the complexities of Indian reality, especially at the urban scale. Admiration for a forceful statement of philosophy is tempered by suspicions of absolutism, and scepticism about the values of the Oxbridge élite that brought Chandigarh into being. In their search for regional identity they look for a greater accommodation of social and spatial ambiguities. The webs of streets in villages and the tight-knit structures and spaces of Jaisalmer have become the revered urban models.

Like the city as a whole, the Capitol monuments excite ambivalence. Those squeamish about monumental statements of power are naturally left uneasy; they revert to facile gestures for filling the spaces between without realizing that this would destroy a place that has a sort of magic in relation to mountains and sky. Arguably the buildings themselves are too grand to house the functions of a mere state capital. But then the original client was not just the local bureaucracy, nor even just Nehru, it was a newly emergent national consciousness which chimed with the hints of a new, post-colonial world order. Le Corbusier chose to celebrate this mood in quasi-sacral terms transcending limited political rhetoric and chauvinism. The ideology that brought the Chandigarh programme into being has slipped away, but the artist saw beyond these transient conditions to themes of longer-range human relevance. The Chandigarh monuments idealize cherished notions of law and government with deep roots: they span the centuries by fusing modern and ancient myths in symbolic forms of prodigious authenticity. Although recent in fabrication they possess a timelessness that will insure them a major place in the stock of cultural memories.